- Home

- Rachel Caine

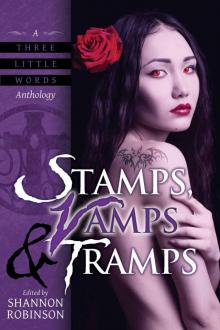

Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology)

Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology) Read online

Published by Evil Girlfriend Media, P.O. BOX 3856, Federal Way, WA 98063

Copyright © 2014

All rights reserved. Any reproduction or distribution of this book, in

part or in whole, or transmission in any form, or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written

permission of the publisher or author is theft.

Any similarity to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

Cover photo by Sabelnikova Olga.

Cover design by Matt Youngmark.

“Easy Mark,” copyright © 2014 by Rachel Caine

“The Whole of His History,” copyright © 2014 by Barbara A. Barnett

“Mungo the Vampire,” copyright © 2014 by Sandra Kasturi

“The Lightning Tree,” copyright © 2014 by Carrie Laben

“Follow Me,” copyright © 2014 by Christine Morgan

“Only Darkness,” copyright © 2014 by Paul Witcover

“Flies in the Ink,” copyright © 2014 by Megan Lee Beals

“The Hungry Living Dead,” copyright © 2014 by Nancy Kilpatrick, reprinted from The Vampire Stories of Nancy Kilpatrick, Mosaic Press, 2000

“Josephine the Tattoo Queen,” copyright © 2014 by Joshua Gage

“Stabilization,” copyright © 2014 by Daniels Parseliti

“A Virgin Hand Disarm’d,” copyright © 2014 by Mary A. Turzillo

“Summer Night in Durham,” copyright © 2014 by Cat Rambo

“His Body Scattered by the Plague Winds,” copyright © 2014 by Adam Callaway

“From the Heart,” copyright © 2014 by Kella Campbell

“Sideponytail,” copyright © 2014 by Lily Hoang

“His Face, All Red,” copyright © 2014 by Gemma Files

ISBN: 978-1495414381

ISBN-10: 1495414388

Dedicated to those eternally tattooed,

By soul-sucking vampires,

Damned to wander the night,

And to only know darkness.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Easy Mark, Rachel Caine

The Whole of His History, Barbara A. Barnett

Mungo the Vampire, Sandra Kasturi

The Lightning Tree, Carrie Laben

Follow Me, Christine Morgan

Only Darkness, Paul Witcover

Flies in the Ink, Megan Lee Beals

The Hungry Living Dead, Nancy Kilpatrick

Josephine the Tattoo Queen, Joshua Gage

Stabilization, Daniels Parseliti

A Virgin Hand Disarm’d, Mary A. Turzillo

Summer Night in Durham, Cat Rambo

His Body Scattered by the Plague Winds, Adam Callaway

From the Heart, Kella Campbell

Sideponytail, Lily Hoang

His Face, All Red, Gemma Files

Biographies

INTRODUCTION

Stamps, vamps, and tramps: from three little words have come sixteen compelling, beautifully crafted stories. Among them, you will find the work of award-winning authors and fan favorites, as well as exciting new talent. In editing this anthology, I was delighted to encounter such a diversity of style and subject matter within the shared triptych of themes.

Across the stories, the “stamps”—that is, the tattoos—are variously protective, punitive, parasitic, totemic, cryptic, funny, and even figurative, making narrative cameos or taking center stage. And yes, two stories feature a classic “tramp stamp.” The “tramps” include the homeless and the restless; the trashy and the titillating; travelers and transgressors of sexual boundaries. And lastly, the “vamps” are a variety of blood-seeking creatures, ranging from a classical, caped seducer in Nancy Kilpatrick’s “The Hungry Living Dead,” to the gherkin-sized fumbler of Sandra Kasturi’s hilarious “Mungo the Vampire,” from femmes fatales to winged monsters, manifesting in psychosis-fueled grotesquerie in Daniels Parseliti’s mental-ward tale, “Stabilization,” and in allusions to pop-culture icons in Lily Hoang’s “Sideponytail,” whose protagonist prefers sexual role-play.

As befits a volume that includes “tramps” in the title, the stories’ settings range widely. “Follow Me,” by Christine Morgan, centers on the risky freedom of street-walking prostitutes in ancient Greece; Mary Turzillo’s “A Virgin Hand Disarm’d” tells of a Renaissance man whose almost-literally burning passion leads him to London. Barbara A. Barnett’s “The Whole of His History” takes place in eighteenth-century America, where a man tries to elude his illicit desires. Rachel Caine’s “Easy Mark,” follows a Depression-era “boxcar boy” (or rather girl, in disguise) in search of a decent meal. “Josephine the Tattoo Queen,” also set in the 1930s, begins in a dark circus side-tent—and where it ends is definitely unlike Water for Elephants. Adam Calloway’s “His Body Scattered” takes us far away, to a lyrical, alternate world named “Lacuna,” where paper can be sacred, magical, sentient… and dangerous.

Two of the stories transpire in tattoo parlors—Cat Rambo’s playful, modern misadventure, “Summer Night in Durham,” and newcomer Megan Beals’ eerie “Flies in the Ink,” set in Tacoma near the end of World War I. Both feature tattoo artists who are reluctant for different reasons in the face of an insistent vampire. Other struggling artists are the protagonists of two sharp urban stories, “From the Heart” by Kella Campbell, and “Only Darkness” by Paul Witcover, which depict, respectively, an exotic dancer in Toronto and a sidewalk portrait-sketcher in New York City, each drawn unwittingly into contact with the supernatural. Carrie Laben’s superbly wry narrative, “The Lightning Tree,” takes place in a rural Northern town that is far from any metropolitan diversions, yet the place is cursed with something far deadlier than just boredom. Gemma Files’ novella, “His Face, All Red” closes the anthology. Hers is a story with relentless momentum: a story of hunting, pilfering, and murdering; of witches, vampires, demons, and family—with some intriguing overlaps in identity.

We at Evil Girlfriend Media are really excited to have brought these stories together for Stamps, Vamps, and Tramps, and we hope that you enjoy reading them as much as we did.

Shannon Robinson, Editor

Baltimore, Maryland

January, 2014

EASY MARK

By Rachel Caine

The sticks arranged close to the back fence were a message Danna could read as easily as printed words: two twigs, arranged like a sideways T. She shifted the bindle on her shoulder in a familiar, automatic gesture, one that had developed over the first week since she’d caught the first boxcar and started developing calluses where the broomstick rubbed—and considered what it meant.

Easy mark.

Even though she was still pretty new at being a Boxcar Boy—and you had to be a boy if you were on the road, like she was—she knew you couldn’t always trust the signs left by other hobos. Tramps were just as good and bad and indifferent as regular folk, and they could be mistaken, or just plain mean. She’d fallen for a false sign on one house that said it was a sit down feed only to find a man with a gun and vicious dog ready to use both on her. So easy mark bothered her. Usually it meant a soft touch, someone kind who’d hand out a good, hot meal and some casual talk, maybe even a bath and a bed if you were real lucky. Luck didn’t hold, though. Things went bad fast, and stayed bad for days or weeks or months or years.

Like it had for her pa.

Danna hadn’t wanted to leave her

family, but she hadn’t had much choice. Her father’s job had been blown away in the dust storms in Oklahoma, where just about every farm had been reduced to desert and sticks; her ma had sickened and died on the road while they’d been trying to make it to California to pick crops. Better she had, really; they’d been told the jobs were in California but when they got there it was nothing but lines of hungry faces waiting.

Someone had to do something if what was left of their family was going to survive.

Her younger brother, Clarence, was too young to be on his own, but she was a solid seventeen, built strong and tall, and flat-chested and thin-hipped. Only natural she’d be the one to go off on her own, so the food would stretch better between her too-thin dad and little Clee. Her father had been stone-faced about it, but she’d seen the tears at the corners of his eyes, and he’d given her some threadbare old pants and a belt to hold them up, and a shirt too big for her but still sturdy enough. She’d had to use her own shoes, but they were farm shoes, built plain and none too girly. Once she’d taken a razor to her hair and reduced it to a short fluff, she passed for a boy just fine. She’d never had nice-girl manners anyway.

She’d had a vague notion of earning some money and sending it for Clee’s care, but she didn’t know where they were now, and anyway, money was powerful hard to come by out here. Today she had a dollar hidden in her shoe, and nothing else but the bindle on her shoulder and a thin, piercing cramp in her stomach.

She had to chance it, this easy mark. She’d been without solid food for three days now; the last hobo jungle she’d tried had been ruled by a cruel old buzzard who’d demanded she go steal a chicken from a farmer down the road if she wanted any mulligan stew. She’d lost the bottle for it when she’d seen the thin, desperate face of the farmer’s wife, and the pathetic skinny chicken—their last one, probably—scratching at the dirt in the yard. Besides, she was no good at catching chickens anyway.

Danna hoisted herself over the wood fence—it wasn’t too tall, and she had long legs, lean and strong from all the wandering—and dropped down on the other side in a crouch, eyes darting all around. No signs of a dog; no lumps of shit on the ground, no bowl of water or food (though she’d known tramps hungry enough to eat the food right out of a dog’s bowl. Many townsfolk wouldn’t even put it out at night anymore for fear of attracting them). The yard was mostly hard-packed dirt, but there was a small vegetable garden growing in the corner, well-tended, and the smell of herbs like rosemary and lavender drifted on the still night air.

Seemed like a nice enough place.

Could dig up a couple of the vegetables and skedaddle, she thought; the idea of a fresh carrot or tomato made her mouth water, and her eyes too. But she wasn’t built to be a thief. Same reason that poor farmer still had his chicken.

It was dangerous, but she walked up to the back door and knocked softly. There was soft light inside behind the lace curtains, but nothing moved for a long moment, and then the curtains shifted aside, and a face looked out.

Danna took a step back—not out of fear, but out of something else she couldn’t really name at all. The man—was it a man that she’d seen?—was big. Big enough to blank out her mind and make her hand shake and grip the bindle-stick tight enough to hurt.

The curtain dropped again, and it was peculiar, but she couldn’t rightly say whether that face had been a man or a woman, old or young, ugly or pretty. Her brain said face and that was all. Like it didn’t know how to deal with it at all.

She was ready to turn and flee when she heard a lock click back, and the door creaked open, and a little old man shuffled out on the step and looked at her with a kind, sad smile.

not him not the face I saw

It was a snatch of nonsense that ran across her mind, and Danna dismissed it firmly like she’d shut away night terrors and so many other things over the years. He was an old man with a kindly, lined face and a shock of unkempt white hair, and light brown eyes the color of the dirt that had swallowed up half the Midwest.

“Hello there,” he said. He had a quiet, Southern voice, deeper than she’d expected. “You lookin’ for a handout?”

“Yessir,” she said, and nodded a little too hard. Somewhere out in the dark, she could hear someone weeping. Far off and very quietly. She knew the sound of despair, and that was it, all right. Didn’t come from inside his house, though. His house seemed like the only sign of warmth and light and kindness in the world, right now.

“Well, come on in, then, you’re lettin’ all the dark inside,” he said, and shuffled back into the house. He had on an old checked robe, one pocket torn and flapping, and under that a well-worn pair of old Levi’s and a work shirt that had seen better days. Slippers on his feet. “I got some stew I can put in a bowl for you, maybe some stuff you can take with you. How you fixed for clothes?”

“Pretty good,” she lied, and came over the threshold into a fairyland of warmth and glimmering light, of clean floors and a polished table and the rich smell of bubbling stew with real meat in it. Her eyes filled with tears, and she felt wrong here, wrong and bad and dirty in this beautiful kitchen. She hadn’t had a wash in so long she knew she smelled like feet and sweat, and her clothes had so much road dirt on them she could almost see it smoking off of her to cloud up the room.

“Make yourself at home,” he said, and waved a palsied old hand at the table and chairs. Three chairs, which was an odd number; most people had two or four, but three seemed uneven. Still, it was a round table and chairs set at a triangle, and maybe it just made sense for him. Maybe he only needed three.

She took one point of the triangle and eased herself down, putting her bindle down on the floor by her feet. She instinctively put a boot on it, as if she was still in a hobo camp where someone might steal it out from under her, but he ignored her as he puttered around the fresh-painted green cabinets and took out a china bowl in dusty pink for the stew. He set it down in front of her with a big, heavy spoon, and as she stared at the hot, steaming meal, thick with fresh carrots and peas and potatoes and chunks of meat, real meat, he cut some slices from a loaf of bread and poured her a china cup of coffee, too.

Danna burst into tears.

She didn’t mean to, but the place, the food, the kindness just overwhelmed her. The tears gave her right away, because however much she looked like a boy she cried like a girl, and she hid her face in her dirty hands as he patted her awkwardly on the shoulder.

“C’mon, gal, let’s get you clean before you fill your stomach. Come on with me, now.”

She stood up, still gasping back sobs, made use of the bar soap and water at the sink. She did her hands and face and neck and arms all the way to the elbows, and the tingle on her skin made her want to weep again. It felt so good to be clean. To be cared for.

He handed her a dish towel, embroidered with little blue flowers at the corner, and she dried herself off and pulled in a full, shaking breath. “Sorry about that,” she said. “I—”

“No need,” he said. “My name’s Riley. Folks ‘round here call me Grandpa Riley. Now, you sit yourself down and get some food in you, you’re shaky as a willow tree. Thin as one, too.”

She took the first bite of the stew and the tears almost came back, because it brought back so much—memories of her mother puttering around the warm little farmhouse kitchen, baking bread, cutting fresh vegetables out of the garden, bestowing kisses on Danna’s head as she stirred the pot. There was love in this stew. She could taste it.

When the old man reached out for his cup, she saw something under his sleeve—a tattoo, maybe, blue ink like old sailors carried on their bodies. It looked strange. Her hunger was making her dizzy, she thought, because it almost seemed to move against his skin.

He wasn’t eating. She stopped long enough to ask, but he waved it aside. “Already did,” he said. “Always keep a little extra on the hob for those in need. You just tuck in.”

She tried to eat slowly, savoring every rich, meaty bite, but all too soon

the bowl was empty, the bread reduced to a thin dusting of crumbs on the teal-blue plate, the good strong coffee drained. She sat for a moment in silence, just taking in the fact that she no longer felt hungry or thirsty or unwanted, and then reached for the plate and the bowl to take them to the sink. He took them first and shuffled over to dunk them in some water. “I’ll wash ‘em later,” he said. “You need more coffee, girl? Hey, what’s your name?”

“Danna,” she said. “Danna MacKay.”

“Out of Oklahoma, I expect. Maybe Texas?”

“Up around Norman, sir, in Oklahoma.”

“How long you been on the road?”

Forever. “About three months or so, I guess.”

“Smart of you to pretend to be a boy, Danna. Too many bad men out there on the road—not that being a pretty young boy’ll always save you either, you know that?”

She did. She’d had a few bad moments; one had been stopped by an older hobo who’d seen it coming, but the other she’d had to get out of on her own, at the point of a knife.

She didn’t want to talk about that. She changed the subject. “You feed a lot of tramps, sir?”

“Grandpa, call me Grandpa. I do what I can. Most fellas are just down on their luck—good folks, just bad circumstances. Ain’t had but a few who thought he could take me for something more than a hot meal and a soft bed.” Grandpa Riley smiled, and for the first time, Danna felt a shiver go up her spine. “Bless their souls.”

“Grandpa—” She started, but then she stopped, because she wasn’t sure what she was asking, really. He seemed to know, though.

“You can stay the night, if you want,” he said. “Got a bathtub for you, and I can get you some fresh clothes. Might be a tad too big on you but girls don’t generally wear the right size on the road, do they? A night in a bed won’t hurt you none. Maybe two, if you want to do some chores. I ain’t as young as I was. Could use some help patching the roof.”

Smoke and Iron

Smoke and Iron Honor Among Thieves

Honor Among Thieves Paper and Fire

Paper and Fire Ash and Quill

Ash and Quill Wolfhunter River (Stillhouse Lake Book 3)

Wolfhunter River (Stillhouse Lake Book 3) Undone

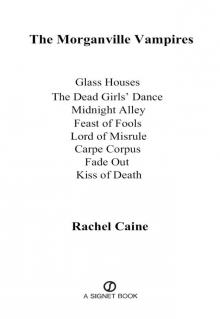

Undone Glass Houses

Glass Houses Prince of Shadows

Prince of Shadows Unseen

Unseen Midnight at Mart's

Midnight at Mart's The Dead Girls Dance

The Dead Girls Dance Last Breath

Last Breath Stillhouse Lake

Stillhouse Lake Daylighters

Daylighters Midnight Alley

Midnight Alley Black Dawn

Black Dawn Fall of Night

Fall of Night Two Weeks Notice

Two Weeks Notice Bitter Blood

Bitter Blood Carpe Corpus

Carpe Corpus Kiss of Death

Kiss of Death Ghost Town

Ghost Town Ill Wind

Ill Wind Fade Out

Fade Out Total Eclipse

Total Eclipse Honor Lost

Honor Lost Thin Air

Thin Air Black Corner

Black Corner Firestorm

Firestorm Bite Club

Bite Club Chill Factor

Chill Factor Windfall

Windfall Oasis

Oasis Devils Bargain

Devils Bargain Terminated

Terminated Feast of Fools

Feast of Fools Lord of Misrule

Lord of Misrule Devils Due

Devils Due Ladies' Night

Ladies' Night Gale Force

Gale Force Heat Stroke

Heat Stroke Killman Creek

Killman Creek Sword and Pen

Sword and Pen Cape Storm

Cape Storm Unbroken

Unbroken Windfall tww-4

Windfall tww-4 Heartbreak Bay (Stillhouse Lake)

Heartbreak Bay (Stillhouse Lake) Daylighters: The Morganville Vampires

Daylighters: The Morganville Vampires Duty

Duty Honor Bound

Honor Bound Unseen os-3

Unseen os-3 Firestorm tww-5

Firestorm tww-5 Blue Crush

Blue Crush Devil s Bargain

Devil s Bargain Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet

Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet Bite Club mv-10

Bite Club mv-10 Terminated tr-3

Terminated tr-3 The Morganville Vampires 14 - Fall of Night

The Morganville Vampires 14 - Fall of Night Bitter Blood tmv-13

Bitter Blood tmv-13 Falling for Grace

Falling for Grace The True Blood of Martyrs

The True Blood of Martyrs Fall of Night (The Morganville Vampires)

Fall of Night (The Morganville Vampires) Devil's Bargain rld-1

Devil's Bargain rld-1 The Morganville Vampires (Books 1-8)

The Morganville Vampires (Books 1-8) Two Weeks' Notice tr-2

Two Weeks' Notice tr-2 An Affinity for Blue

An Affinity for Blue Caine, Rachel-Short Stories

Caine, Rachel-Short Stories Kiss of Death tmv-8

Kiss of Death tmv-8 WITCHGRAVE

WITCHGRAVE Dark Rides

Dark Rides The Morganville Vampires

The Morganville Vampires Killman Creek (Stillhouse Lake Series Book 2)

Killman Creek (Stillhouse Lake Series Book 2) Midnight Bites

Midnight Bites Line of Sight

Line of Sight![Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/morganville_vampires_01_glass_houses_preview.jpg) Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses

Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses Black Dawn tmv-12

Black Dawn tmv-12 Midnight at Mart ww-103

Midnight at Mart ww-103 Feast of Fools tmv-4

Feast of Fools tmv-4 Ill Wind tww-1

Ill Wind tww-1 Devil's Due rld-2

Devil's Due rld-2 Black Dawn: The Morganville Vampires

Black Dawn: The Morganville Vampires Dead Girls' Dance tmv-2

Dead Girls' Dance tmv-2 Minute Maids

Minute Maids Carpe Corpus tmv-6

Carpe Corpus tmv-6 Total Eclipse tww-9

Total Eclipse tww-9 Ghost Town mv-9

Ghost Town mv-9 Lord of Misrule tmv-5

Lord of Misrule tmv-5 Faith Like Wine

Faith Like Wine Two Weeks' Notice: A Revivalist Novel

Two Weeks' Notice: A Revivalist Novel Daylighters tmv-15

Daylighters tmv-15 Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology)

Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology) Unbroken os-4

Unbroken os-4 Unknown os-2

Unknown os-2 4 - Unbroken

4 - Unbroken Cape Storm tww-8

Cape Storm tww-8 Last Breath tmv-11

Last Breath tmv-11 Midnight Alley tmv-3

Midnight Alley tmv-3 Glass Houses tmv-1

Glass Houses tmv-1 Fade Out tmv-7

Fade Out tmv-7 Fall of Night tmv-14

Fall of Night tmv-14 Godfellas

Godfellas Heat Stroke ww-2

Heat Stroke ww-2 Carniepunk

Carniepunk Oasis ww-102

Oasis ww-102 Gale Force tww-7

Gale Force tww-7 Working Stiff tr-1

Working Stiff tr-1