- Home

- Rachel Caine

Fade Out tmv-7 Page 2

Fade Out tmv-7 Read online

Page 2

“So not the point!”

“Oh, pish. It’s just another living creature,” Myrnin said, and put his hand out. The spider waved its front legs uncertainly, then carefully stepped up on his pale fingers. “Nothing to be frightened of, if handled properly.” He lightly stroked the furry back of the thing, and Claire nearly passed out. “I think I’ll call him Bob. Bob the spider.”

“You’re insane.”

Myrnin glanced up and smiled, dimples forming in his face. It should have looked cute, but his smiles were never that simple. This one carried hints of darkness and arrogance. “But I thought that was part of my charm,” he said, and lifted Bob the spider carefully to take him off to another part of the lab. Claire didn’t care what he did with the thing, as long as he didn’t wear it as an earring or a hat or something.

Not that she’d put that past him.

She was very careful as she folded back the old cardboard. No relatives of Bob appeared, at least. The contents of the box were a tangle of confusion, and it took her time to sort out the pieces. There were balls of ancient twine, some coming undone in stiff spirals; a handful of what looked like very old lace, with gold edging; two carved, yellowing elephants, maybe ivory.

The next layer was paper—loose paper made stiff and brittle and dark with age. The writing on the pages was beautiful, precise, and very dense, but it wasn’t Myrnin’s hand; she knew how he wrote, and it was far messier than this. She began reading the first paper.

My dear friend, I have been in New York for some years now, and missing you greatly. I know that you were angry with me in Prague, and I do not blame you for it. I was hasty and unwise in my dealings with my father, but I honestly do believe that he left me little choice. So, dear Myrnin, I beg you, undertake a journey and come to visit. I know travel no longer agrees with you, but I think if I spend another year alone, I will give up entirely. I would call it a great favor if you would visit.

It was signed, with an ornate flourish, Amelie.

As in, Amelie, Founder of Morganville, and Claire’s ultimate—although she didn’t like to think of it this way—boss/owner.

Before Claire could open her mouth to ask, Myrnin’s cool white fingers reached over her shoulder and plucked the page neatly from her hand. “I said determine if we can use these things, not read my private mail,” he said.

“Hey—was that why you came to America? Because she wrote to you?”

Myrnin looked down at the paper for a moment, then crumpled it into a ball and threw it in a large plastic trash bin against the wall. “No,” he said. “I didn’t come when she asked me. I came when I had to.”

“When was that?” Claire didn’t bother to protest how unfair it was that he wanted her to not read things to figure out if they needed them. Or that since he’d kept the letter all this time, he should think before throwing it away.

She just reached for the next loose page in the box.

“I arrived about five years after she wrote to me,” Myrnin said. “In other words, too late.”

“Too late for what?”

“Are you simply going to badger me with personal questions, or are you planning to do what I told you to do?”

“Doing it,” Claire pointed out. Myrnin was irritated, but that didn’t bother her, not anymore. She didn’t take anything he said personally. “And I do have the right to ask questions, don’t I?”

“Why? Because you put up with me?” He waved his hand before she could respond. “Yes, yes, all right. Amelie was in a bad way in those days—she had lost everything, you see, and it’s hard for us to start over and over and over. Eternal youth doesn’t mean you don’t get tired of the constant struggles. So . . . by the time she wrote to me again, she had done something quite insane.”

“What?”

He made a vague gesture around him. “Look around you.”

Claire did. “Um . . . the lab?”

“She bought the land and began construction on the town of Morganville. It was meant to be a refuge for our people, a place we could live openly.” He sighed. “Amelie is quite stubborn. By the time I arrived to tell her it was a fool’s errand, she was already committed to the experiment. All I could do was mitigate the worst of it, so that she wouldn’t get us all slaughtered.”

Claire had forgotten all about the box (and even Bob the spider), so focused was she on Myrnin’s voice, but when he paused, she remembered, and reached in again to pull out an ornate gold hand mirror. It was definitely girly, and besides, the glass was shattered in the middle, only a few silvery pieces still remaining. “Trash?” she asked, and held it up. Myrnin plucked it out of her hand and set it aside.

“Most definitely not,” he said. “It was my mother’s.”

Claire blinked. “You had a—” Myrnin’s wide stare challenged her to just try to finish that sentence, and she surrendered. “Wow, okay. What was she like? Your mother?”

“Evil,” he said. “I keep this to keep her spirit away.”

That made . . . about as much sense as most things Myrnin said, so Claire let it go. As she rummaged through the stuff in the box—mostly more papers, but a few interesting trinkets—she said, “So, are you looking for something in particular, or just looking?”

“Just looking,” he said, but she knew that tone in his voice, and he was lying. The question was, was he lying for a reason, or just for fun? Because with Myrnin, it could go either way.

Claire’s fingers closed on something small—a delicate gold chain. She pulled, and slowly, a necklace came out of the mess of paper, and spun slowly in the light. It was a locket, and inside was a small, precise portrait of a Victorian-style young woman. There was a lock of hair woven into a tiny braid around the edges, under the glass.

Claire rubbed the old glass surface with her thumb, frowning, and then recognized the face staring back at her. “Hey! That’s Ada!”

Myrnin grabbed the necklace, stared for a moment at the portrait, and then closed his eyes. “I thought I’d lost this,” he said. “Or perhaps I never had it in the first place. But here she is, after all.”

And just like that, Ada flickered into being across the room. She wasn’t alive, not anymore. Ada was a two-dimensional image, a kind of projection, from the weird steampunk computer located beneath Myrnin’s lab; that computer was the actual Ada, including parts of the original girl. Ada’s image still wore Victorian skirts and a high-necked blouse, and her hair was up in a complicated bun, leaving wisps around her face. She didn’t look quite right—more like a really good computer generation of a person than a person. “My picture,” she said. Her voice was weirdly electronic because it used whatever speakers were around; Claire’s phone became part of the surround sound experience, which was so creepy that she automatically reached down and switched it off.

Ada sent her a dark look as the ghost swept through things in her way—tables, chairs, lights.

“Yes,” Myrnin said, as calmly as if he spoke to electronic ghosts every day—which, in fact, he did.“I thought I’d lost it. Would you like to see it?”

Ada stopped, and her image floated in the air in the middle of an open expanse of the floor without casting a shadow. “No,” she said. Without Claire’s phone adding to the mix, her voice came out of an ancient radio speaker in the back of the lab, faint and scratchy. “No need. I remember the day I gave it to you.”

“So do I.” Myrnin’s voice remained quiet, and Claire couldn’t honestly tell if what they were talking about was a good memory, or a bad one.

“Why were you looking for it?”

“I wasn’t.” That, Claire was almost sure, was another lie. “Ada, I asked you to please stop coming here, except when I call you. What if I’d had other visitors?”

Ada’s delicate, not-quite-living face twisted into an expression of contempt. “Who would visit you?”

“An excellent point.” His tone cooled and hardened and took on edges. “I don’t want you coming here unless I call you. Are we understood,

or do I have to come and alter your programming? You won’t thank me for it.”

She glared at him with eyes made of static and ice, and finally turned—a two-dimensional turn, like a cardboard cutout—and flashed at top speed through the solid wall.

Gone.

Myrnin let out a slow breath.

“What the heck was that?” Claire asked. Ada creeped her out, and besides, Ada really didn’t like her. Claire was, in some sense, a rival for Myrnin’s attention, and Ada . . .

Ada was kind of in love with him.

Myrnin looked down at the necklace and the portrait lying flat in his palm. For a moment, he didn’t say anything, and Claire honestly thought he wouldn’t bother. Then, without looking up, he said, “I did care for her, you know.” She thought he was saying it to himself more than to her. “Ada wanted me to turn her, and I did. She was with me for almost a hundred years before . . .”

Before he snapped one day, Claire thought. And Ada died before he could stop himself. Myrnin had told her the first day she’d met him that he was dangerous to be around, and that he’d gone through a lot of assistants.

Ada had been the first one he’d killed.

“It wasn’t your fault,” Claire heard herself saying. “You were sick.”

Myrnin’s shoulders moved just a little, up and down—a shrug, a very small one. “It’s an explanation, not an excuse,” he said, and looked up at her. She was a little startled by what she saw—he almost looked, well, human.

And then it was gone. He straightened, slid the necklace into the pocket of his vest, and nodded toward the box. “Continue,” he said. “There may yet be something more useful than sentimental nonsense in there.”

Ouch. She didn’t even like Ada, and that still stung. She hoped the computer—the computer that held Ada’s still-sort-of-living brain—wasn’t listening.

Fat chance.

The afternoon passed. Claire learned to scan the sheets of paper instead of read them; mostly, they were just letters, an archive of Myrnin’s friendship with people long gone, or vampires still around. A lot were from Amelie, over the years—interesting, but it was all still history, and history equaled boring.

It wasn’t until she was almost to the bottom of the second box that she found something she didn’t recognize. She picked up the odd-shaped thing—sculpture?—and sat it on her palm. It was metal, but it was surprisingly light. Kind of a faintly rusty sheen, but it definitely wasn’t iron. It was etched with symbols, some of which she recognized as alchemical. “What’s this?”

Before the words were out of her mouth, her palm was empty, Myrnin was across the room, and he was turning the weird little object over and over in his hands, fingers gliding over every angle and trembling on the outlined symbols. “Yes,” he whispered, and then louder, “Yes!” He bounced in place, for all the world like Eve with her Blanche DuBois note, and stopped to wave the thing at Claire. “You see?”

“Sure,” she said. “What is it?”

His lips parted, and for a second she thought he was going to tell her, but then some crafty little light came into his eyes, and he closed his hand around the sharp outlines of the thing. “Nothing,” he purred. “Pray continue. I’ll be—over here.” He moved to an area of the lab where he had a reading corner with a big leather armchair and a stained-glass lamp. He carefully moved the chair so its back was toward her, and plunked himself down with his bunny-slippered feet up on a hassock to examine his find.

“Freak,” she sighed.

“I heard that!”

“Good.” Claire sawed through the ropes on the next-to-last box.

It exploded.

2

When Claire opened her eyes again, she saw three faces looming over her. One was Myrnin’s, and he looked concerned. One was the shining blond head of her housemate Michael Glass—Michael had her hand in his, which was nice, because he was sweet, and he had beautiful hands, too. The last face took her a moment, and then recognition clicked into place. “Oh,” Claire murmured. “Hello, Dr. Theo.”

“Hello, Claire,” said Theo Goldman, and put a finger to his lips. He was a kind-looking older man, a bit frayed around the edges, and he had an antique black stethoscope in his ears. He was listening to her heart. “Ah. Very good. Your heart is still beating, I’m sure you’ll be very pleased to hear.”

“Yay,” Claire said, and tried to sit up. That was a bad idea, and Michael had to support her when she lost her balance. The headache hit a moment later, massive as a hurricane inside her skull. “Ow?”

“You struck your head when you fell,” Theo said. “I don’t believe there’s any permanent damage, but you should see your physician and have the tests done. I should hate to think I missed anything.”

Claire pulled in a deep breath. “Maybe I should see Dr. Mills. Just in case—hey, wait. Why did I fall?”

They all exchanged looks. “You don’t remember?” Michael asked.

“Why? Is that bad? Is that brain damage?”

“No,” Theo said firmly, “it is quite natural to have some loss of memory around such an event.”

“What kind of event?” There it was again, that silence, and Claire raised her personal terror alert from yellow to orange. “Anybody?”

Myrnin said, “It was a bomb.”

She blinked, not entirely sure she’d heard him right. “A bomb. Are you sure you understand what that is? Because—” She gestured vaguely at herself, then around at the room, which looked pretty much untouched. All glassware intact. “Because generally bombs go boom.”

“It was a light bomb,” Myrnin said. “Touch your face.”

Now that she thought about it, her face did feel a bit hot. She put her fingers on her cheeks.

Burning hot. “What happened to me?” She couldn’t keep the fear out of her voice.

Theo and Michael both tried to talk at once, but Michael won. “It’s like a sunburn,” he said. “Your face is a little pink, that’s all.”

Michael wasn’t a very good liar. “Great. I’m red as a cherry, right?”

“Not at all,” Myrnin said cheerfully. “You’re definitely not as red as a cherry. Or an apple. Yet. That will take some time.”

Claire tried to focus back on what was—hopefully—more important. “A light bomb?”

Myrnin looked suddenly a great deal more serious. “It’s an inconvenience for a human,” he said. “It would have been extremely damaging to me, or to any vampire, had I been the one to open the box.”

“So who sent you a bomb?”

He shrugged. “Eh, it was so long ago. Might have been Klaus. But I might have actually sent it to myself. I’m not always that rational, you know. Mind you, I wouldn’t open the last box if I were you.”

Claire sent him a long, wordless look, then accepted the hand Michael extended to help her to her feet. She felt dizzy and—yes—sunburned, and a whole lot filthy. “Great. You might have booby-trapped your own boxes. Why would you do a thing like that?”

“Excellent question.” Myrnin left her and went to the table, where he lifted from the open box a complicated-looking tangle of metal and wires—the kind of bomb an insane Victorian inventor might have made—and set it very carefully to one side. “I can only think that I meant it to protect what else was in the container.”

He stood there staring into the box, not moving, and Claire finally rolled her eyes and said, “Well?”

“What?”

“What’s in the box, Myrnin?”

In answer, he tipped it over in her direction. A cloud of dust fogged the air, and when it cleared, Claire saw that there was nothing in the box.

Nothing at all.

“I’m going home,” she sighed. “This job sucks.”

Michael gave her a ride back to the Glass House, which was what she meant when she said home, although technically she didn’t live there. Technically, her parents had a room for her in their house, and her stuff was there. Mostly. Well, partly. And, according to the agreemen

t she’d reached with them, she slept there most every night—for a few hours, anyway.

It was all part of her parents’ grand scheme to keep her and Shane—well, maybe apart was too harsh.

Casual.

They didn’t want their little girl shacking up with the town bad boy, even though Shane was not the town bad boy, and he and Claire were in love.

In love.

That still gave her a delicious little tingle every time she thought about it.

“Parents,” Claire said aloud. Michael sent her a look.

“And?”

“They bring the crazy,” she said. “Is Shane home?”

“Not yet. I dropped Eve off at her first rehearsal.” He smiled slowly. “Was she that excited when she got the letter?”

“Define excited. You mean, did she look like a cartoon character on crack? Yes. I never knew she was all into acting and stuff.”

“She loves it. She’s always acting out scenes from movies and TV shows in her room. When we were in high school, she used to organize these little plays in study hall, give us all parts she’d written out on little pieces of paper, and the teacher never knew what the hell was going on. Insane, but fun.” Michael braked his car; Claire couldn’t see beyond the tinted windows, but she assumed there was some kind of red light. Good thing Michael had special vampire vision, or they’d be exchanging insurance with some other driver right about now. “So this is a big deal for her.”

“Yeah, I got that. Speaking of big deals, I heard that you’re playing at the TPU theater tomorrow.”

The tips of his ears got a little pink, which (even in a vampire) was adorable. “Yeah, apparently they heard about the last three sets at Common Grounds.” Those had been pretty spectacular events, Claire had to admit—people jammed in shoulder to shoulder, including an impressive number of vampires all playing nice, at least for the evening. “Not a big deal.”

Smoke and Iron

Smoke and Iron Honor Among Thieves

Honor Among Thieves Paper and Fire

Paper and Fire Ash and Quill

Ash and Quill Wolfhunter River (Stillhouse Lake Book 3)

Wolfhunter River (Stillhouse Lake Book 3) Undone

Undone Glass Houses

Glass Houses Prince of Shadows

Prince of Shadows Unseen

Unseen Midnight at Mart's

Midnight at Mart's The Dead Girls Dance

The Dead Girls Dance Last Breath

Last Breath Stillhouse Lake

Stillhouse Lake Daylighters

Daylighters Midnight Alley

Midnight Alley Black Dawn

Black Dawn Fall of Night

Fall of Night Two Weeks Notice

Two Weeks Notice Bitter Blood

Bitter Blood Carpe Corpus

Carpe Corpus Kiss of Death

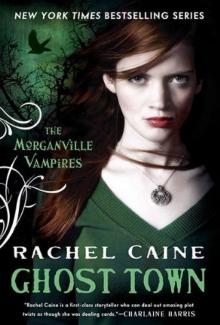

Kiss of Death Ghost Town

Ghost Town Ill Wind

Ill Wind Fade Out

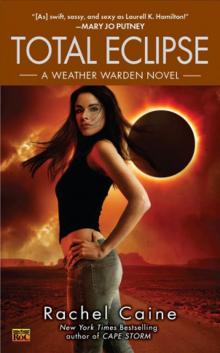

Fade Out Total Eclipse

Total Eclipse Honor Lost

Honor Lost Thin Air

Thin Air Black Corner

Black Corner Firestorm

Firestorm Bite Club

Bite Club Chill Factor

Chill Factor Windfall

Windfall Oasis

Oasis Devils Bargain

Devils Bargain Terminated

Terminated Feast of Fools

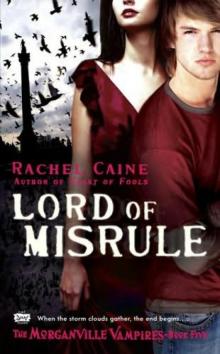

Feast of Fools Lord of Misrule

Lord of Misrule Devils Due

Devils Due Ladies' Night

Ladies' Night Gale Force

Gale Force Heat Stroke

Heat Stroke Killman Creek

Killman Creek Sword and Pen

Sword and Pen Cape Storm

Cape Storm Unbroken

Unbroken Windfall tww-4

Windfall tww-4 Heartbreak Bay (Stillhouse Lake)

Heartbreak Bay (Stillhouse Lake) Daylighters: The Morganville Vampires

Daylighters: The Morganville Vampires Duty

Duty Honor Bound

Honor Bound Unseen os-3

Unseen os-3 Firestorm tww-5

Firestorm tww-5 Blue Crush

Blue Crush Devil s Bargain

Devil s Bargain Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet

Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet Bite Club mv-10

Bite Club mv-10 Terminated tr-3

Terminated tr-3 The Morganville Vampires 14 - Fall of Night

The Morganville Vampires 14 - Fall of Night Bitter Blood tmv-13

Bitter Blood tmv-13 Falling for Grace

Falling for Grace The True Blood of Martyrs

The True Blood of Martyrs Fall of Night (The Morganville Vampires)

Fall of Night (The Morganville Vampires) Devil's Bargain rld-1

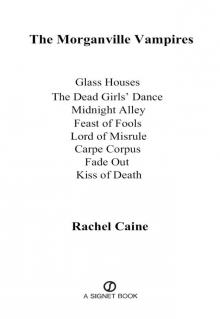

Devil's Bargain rld-1 The Morganville Vampires (Books 1-8)

The Morganville Vampires (Books 1-8) Two Weeks' Notice tr-2

Two Weeks' Notice tr-2 An Affinity for Blue

An Affinity for Blue Caine, Rachel-Short Stories

Caine, Rachel-Short Stories Kiss of Death tmv-8

Kiss of Death tmv-8 WITCHGRAVE

WITCHGRAVE Dark Rides

Dark Rides The Morganville Vampires

The Morganville Vampires Killman Creek (Stillhouse Lake Series Book 2)

Killman Creek (Stillhouse Lake Series Book 2) Midnight Bites

Midnight Bites Line of Sight

Line of Sight![Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/morganville_vampires_01_glass_houses_preview.jpg) Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses

Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses Black Dawn tmv-12

Black Dawn tmv-12 Midnight at Mart ww-103

Midnight at Mart ww-103 Feast of Fools tmv-4

Feast of Fools tmv-4 Ill Wind tww-1

Ill Wind tww-1 Devil's Due rld-2

Devil's Due rld-2 Black Dawn: The Morganville Vampires

Black Dawn: The Morganville Vampires Dead Girls' Dance tmv-2

Dead Girls' Dance tmv-2 Minute Maids

Minute Maids Carpe Corpus tmv-6

Carpe Corpus tmv-6 Total Eclipse tww-9

Total Eclipse tww-9 Ghost Town mv-9

Ghost Town mv-9 Lord of Misrule tmv-5

Lord of Misrule tmv-5 Faith Like Wine

Faith Like Wine Two Weeks' Notice: A Revivalist Novel

Two Weeks' Notice: A Revivalist Novel Daylighters tmv-15

Daylighters tmv-15 Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology)

Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology) Unbroken os-4

Unbroken os-4 Unknown os-2

Unknown os-2 4 - Unbroken

4 - Unbroken Cape Storm tww-8

Cape Storm tww-8 Last Breath tmv-11

Last Breath tmv-11 Midnight Alley tmv-3

Midnight Alley tmv-3 Glass Houses tmv-1

Glass Houses tmv-1 Fade Out tmv-7

Fade Out tmv-7 Fall of Night tmv-14

Fall of Night tmv-14 Godfellas

Godfellas Heat Stroke ww-2

Heat Stroke ww-2 Carniepunk

Carniepunk Oasis ww-102

Oasis ww-102 Gale Force tww-7

Gale Force tww-7 Working Stiff tr-1

Working Stiff tr-1