- Home

Page 4

Page 4

Smoke and Iron

Smoke and Iron Honor Among Thieves

Honor Among Thieves Paper and Fire

Paper and Fire Ash and Quill

Ash and Quill Wolfhunter River (Stillhouse Lake Book 3)

Wolfhunter River (Stillhouse Lake Book 3) Undone

Undone Glass Houses

Glass Houses Prince of Shadows

Prince of Shadows Unseen

Unseen Midnight at Mart's

Midnight at Mart's The Dead Girls Dance

The Dead Girls Dance Last Breath

Last Breath Stillhouse Lake

Stillhouse Lake Daylighters

Daylighters Midnight Alley

Midnight Alley Black Dawn

Black Dawn Fall of Night

Fall of Night Two Weeks Notice

Two Weeks Notice Bitter Blood

Bitter Blood Carpe Corpus

Carpe Corpus Kiss of Death

Kiss of Death Ghost Town

Ghost Town Ill Wind

Ill Wind Fade Out

Fade Out Total Eclipse

Total Eclipse Honor Lost

Honor Lost Thin Air

Thin Air Black Corner

Black Corner Firestorm

Firestorm Bite Club

Bite Club Chill Factor

Chill Factor Windfall

Windfall Oasis

Oasis Devils Bargain

Devils Bargain Terminated

Terminated Feast of Fools

Feast of Fools Lord of Misrule

Lord of Misrule Devils Due

Devils Due Ladies' Night

Ladies' Night Gale Force

Gale Force Heat Stroke

Heat Stroke Killman Creek

Killman Creek Sword and Pen

Sword and Pen Cape Storm

Cape Storm Unbroken

Unbroken Windfall tww-4

Windfall tww-4 Heartbreak Bay (Stillhouse Lake)

Heartbreak Bay (Stillhouse Lake) Daylighters: The Morganville Vampires

Daylighters: The Morganville Vampires Duty

Duty Honor Bound

Honor Bound Unseen os-3

Unseen os-3 Firestorm tww-5

Firestorm tww-5 Blue Crush

Blue Crush Devil s Bargain

Devil s Bargain Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet

Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet Bite Club mv-10

Bite Club mv-10 Terminated tr-3

Terminated tr-3 The Morganville Vampires 14 - Fall of Night

The Morganville Vampires 14 - Fall of Night Bitter Blood tmv-13

Bitter Blood tmv-13 Falling for Grace

Falling for Grace The True Blood of Martyrs

The True Blood of Martyrs Fall of Night (The Morganville Vampires)

Fall of Night (The Morganville Vampires) Devil's Bargain rld-1

Devil's Bargain rld-1 The Morganville Vampires (Books 1-8)

The Morganville Vampires (Books 1-8) Two Weeks' Notice tr-2

Two Weeks' Notice tr-2 An Affinity for Blue

An Affinity for Blue Caine, Rachel-Short Stories

Caine, Rachel-Short Stories Kiss of Death tmv-8

Kiss of Death tmv-8 WITCHGRAVE

WITCHGRAVE Dark Rides

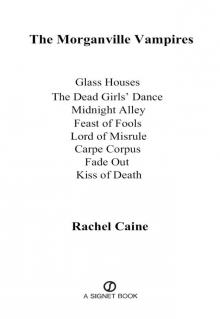

Dark Rides The Morganville Vampires

The Morganville Vampires Killman Creek (Stillhouse Lake Series Book 2)

Killman Creek (Stillhouse Lake Series Book 2) Midnight Bites

Midnight Bites Line of Sight

Line of Sight![Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/morganville_vampires_01_glass_houses_preview.jpg) Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses

Morganville Vampires [01] Glass Houses Black Dawn tmv-12

Black Dawn tmv-12 Midnight at Mart ww-103

Midnight at Mart ww-103 Feast of Fools tmv-4

Feast of Fools tmv-4 Ill Wind tww-1

Ill Wind tww-1 Devil's Due rld-2

Devil's Due rld-2 Black Dawn: The Morganville Vampires

Black Dawn: The Morganville Vampires Dead Girls' Dance tmv-2

Dead Girls' Dance tmv-2 Minute Maids

Minute Maids Carpe Corpus tmv-6

Carpe Corpus tmv-6 Total Eclipse tww-9

Total Eclipse tww-9 Ghost Town mv-9

Ghost Town mv-9 Lord of Misrule tmv-5

Lord of Misrule tmv-5 Faith Like Wine

Faith Like Wine Two Weeks' Notice: A Revivalist Novel

Two Weeks' Notice: A Revivalist Novel Daylighters tmv-15

Daylighters tmv-15 Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology)

Stamps, Vamps & Tramps (A Three Little Words Anthology) Unbroken os-4

Unbroken os-4 Unknown os-2

Unknown os-2 4 - Unbroken

4 - Unbroken Cape Storm tww-8

Cape Storm tww-8 Last Breath tmv-11

Last Breath tmv-11 Midnight Alley tmv-3

Midnight Alley tmv-3 Glass Houses tmv-1

Glass Houses tmv-1 Fade Out tmv-7

Fade Out tmv-7 Fall of Night tmv-14

Fall of Night tmv-14 Godfellas

Godfellas Heat Stroke ww-2

Heat Stroke ww-2 Carniepunk

Carniepunk Oasis ww-102

Oasis ww-102 Gale Force tww-7

Gale Force tww-7 Working Stiff tr-1

Working Stiff tr-1